Este mês a newsletter é um pouco diferente do habitual. Há um ano atrás submeti este “ensaio-desenhado” para o Center for Humans and Nature.

Na altura não foi escolhido para publicação e ficou guardado na “gaveta”. Trabalhei nele durante 3 meses e foi um projecto que me deu imenso prazer fazer — expandi os meus horizontes durante o tempo das investigações e pesquisas, li, escrevi e desenhei e foi feito no lugar onde vivo com os seres que me rodeiam. Com ele aprofundei a relação com a comunidade do vale de que faço parte e guardei práticas e aprendizagens que são agora parte da minha vivência aqui.

Maio é o mês em que nasci e achei que fazia sentido partilhá-lo aqui convosco como numa pequena celebração. Convido-vos assim a lê-lo.

Nota: o ensaio desenhado foi escrito originalmente em inglês e por essa razão é dessa forma que o partilho aqui, mas junto em baixo a versão em Português do texto para quem preferir ler assim.

*

This month’s newsletter is a little different from usual. A year ago, I submitted this "illustrated essay" to the Center for Humans and Nature.

At the time, it wasn’t selected for publication, so it stayed tucked away in the "drawer". I worked on it for three months, and it was a project that brought me immense joy—I expanded my horizons during the research process, reading, writing, and drawing, all done in the place I call home, surrounded by the beings that live here with me. Through it, I deepened my connection with the valley community I’m part of, and I preserved practices and lessons that are now woven into my life here.

May is the month I was born, and I thought it made sense to share it with you here as a small celebration. So, I invite you to read it.

Note: The illustrated essay was originally written in English, which is why I’m sharing it in that form, but I’ve included the Portuguese version of the text below for those who’d prefer to read it that way.

Edible Herbarium – a learning journey

When I was a child, the pine forest next to my aunt and uncle’s house, where I spent my holidays, was my refuge. I played freely, ran over the pine needles, quietly listened to the sounds of the wind and birds and, around the solid and rough trunks of the pine trees, I collected the pine cones which I would shake curiously to find their seeds – the pine nuts. A treat I enjoyed during the hours I spent there. When I saw drops of resin appear in the crevices of the trunk, I touched them with my little fingers, I found that translucent liquid that looked like honey beautiful, and I ended up with sticky fingers that clung to everything I touched: dust, pine needles, soil, moss. That pine forest is a memory of love and comfort that still lives within me today, a community of beings, a safe place where I could be myself and feel good. Even today, if I need to calm down, it is the first image that forms inside me: the canopy of a pine tree, full of needles, pine cones, and sunlight, the trunk and my hand on its bark, feet on the pine needles, smelling the scent of moss and damp earth. The other memories I have, where love is manifested in comfort, sharing, and food, are with my grandparents, and today, already in middle age, I add the ones I created in our home with my son.

I have been living for six years in this urban space (in the city of Lisbon), next to a small valley crossed by a creek. The beings that live here are part of my days – the plants, the birds, the frogs, and other animals, the stones. I am attentive and present, also curious. Throughout the seasons of the year, I learn their rhythms, we share silent dialogues and various moments of life: pains, distresses, joys. So many times, they surprise me with awe.

“Sometimes I need

only to stand

wherever I am

to be blessed.”

Mary Oliver, from the poem “It was early” in “Devotions - The Selected Poems of Mary Oliver”

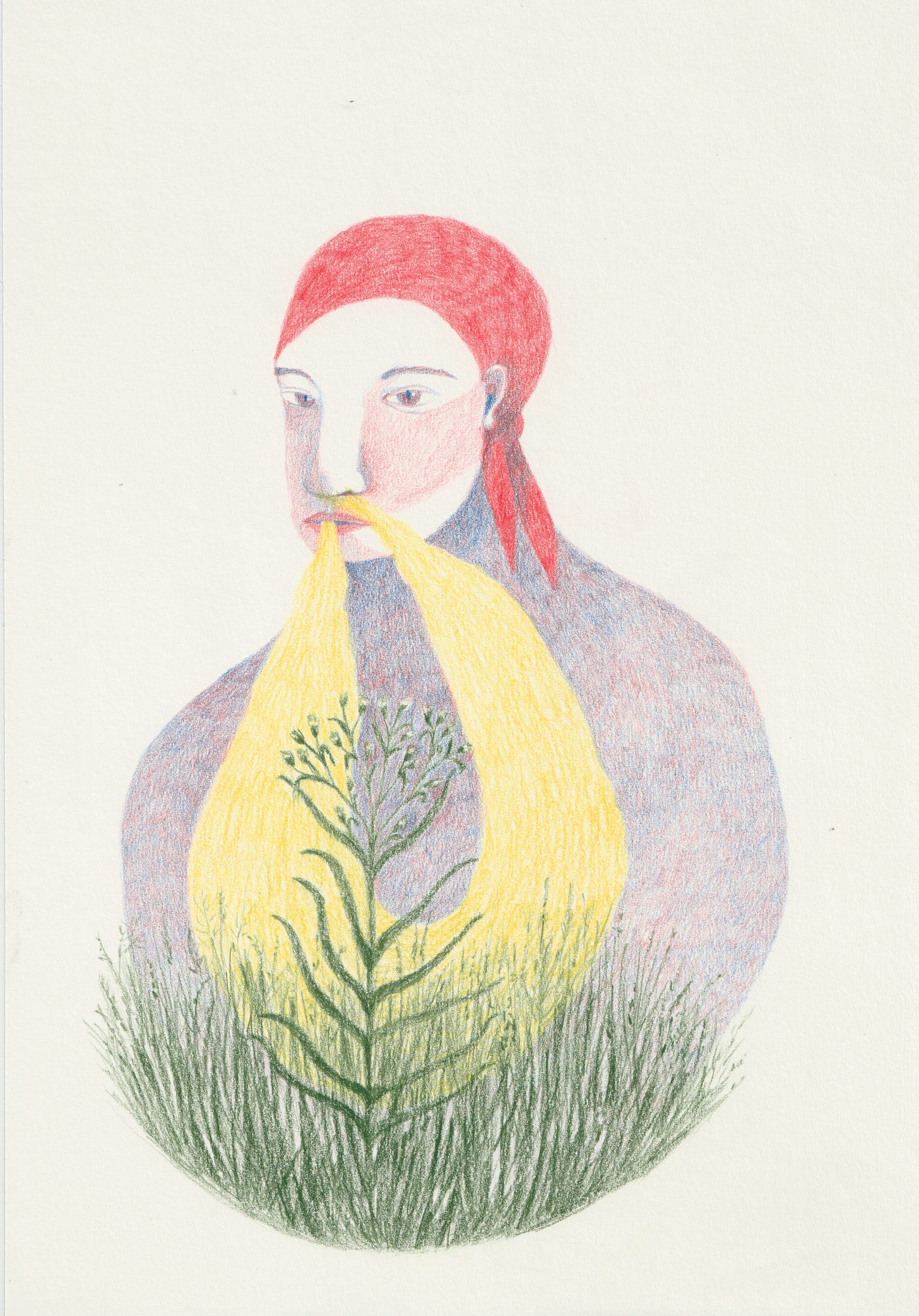

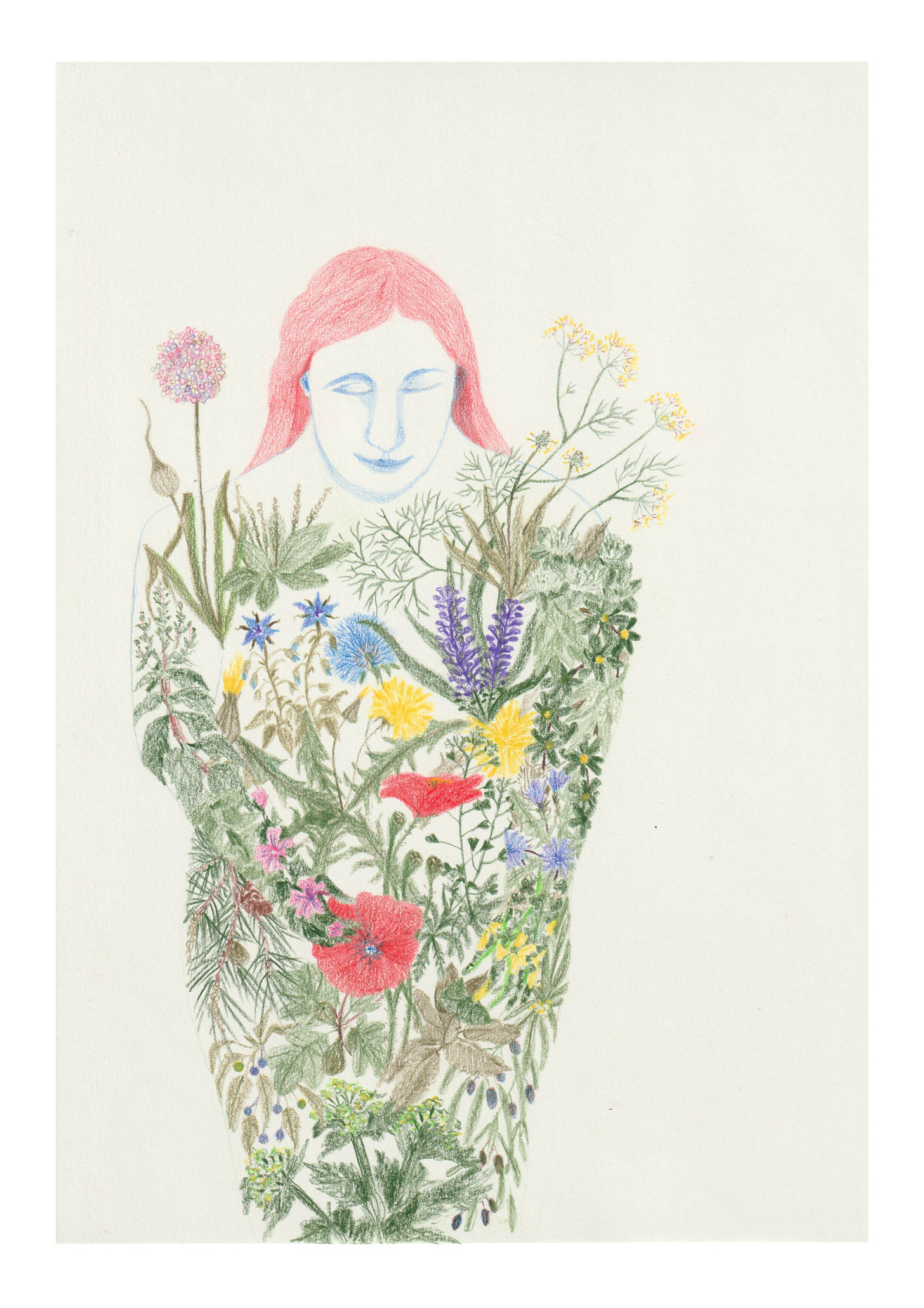

This community I am part of is my life experience, and the drawings I create are the expression of the experience of living here – observations and interpretations, also “imaginations” and other utopias arise from these shared moments.

This practice, which erratically has always been part of my life since childhood, solidified with the move to this place and the coexistence with all the beings that surround me. It is now part of my life and is also a way to counteract the alienation and rootlessness that isolate and surround us.

The plants are around me; they are the ones I greet first thing in the morning from the window, they greet me, accompany me when I walk through the valley, we are always side by side. Inside me, the pine forest, outside me, all the plants. We breathe together, they are part of us, form the atmosphere, we inhale and exhale a common breath that gives us life. Receiving and giving, giving and receiving, the plants nourish us and provide us with sustenance, they treat us and heal us.

“To all cultures, beliefs form and explain the human-nature relationship. Beliefs help a person recognize his/her link to the natural world and his/her responsibility to ensure its survival. No person is truly connected to the natural world or to his/her culture if he/she does not maintain physical, social, spiritual, and mental health; together, they form the breath of life. Breath is the matter and energy, which indigenous people believe moves in all living things. Maintaining a balanced and pure human breath also ensures the purity and health of the breath of the natural world.

With the awareness that one’s breath is shared by all surrounding life, that one’s emergence into this world was possibly caused by some of the life-forms around one’s environment, and that one is responsible for its mutual survival, it becomes apparent that it is related to you; that it shares a kinship with you and with all humans, as does a family or tribe. A reciprocal relationship has been fostered with the realization that humans affect nature and nature affect humans. This awareness influences indigenous interactions with the environment. It is these interactions, these cultural practices of living with a place, that are manifestations of kincentric ecology.”

Enrique Salmón, “Kincentric ecology: indigenous perceptions of the human-nature relationship”

“At each inhalation, free oxygen breathed out by plants enters us in all its levity and allows us to convert what we eat into energy. At each exhalation, we let go of carbon dioxide and water, which plants ingeniously combine with a touch of sunlight to make their own food and, once again, more oxygen. Excitedly, she continued by pointing out how we breathe each other in and out of existence, one made by the exhalation of the other. Arising from perfect stillness, this deep breath of fresh air is the necessary movement that brings innovation and the expression of individuality, where the unique and the separate as the plant and the human are made temporarily possible. And this same inspired movement that generated them also unbinds them, incessantly releasing both the plant and the human into a space where the separate parts are dissolved.”

Monica Gagliano, “Thus Spoke the Plant”

I return to the pine forest of my childhood. I have the pine cone in my hand, I shake it, and three pine nuts fall out. I dirty my hands with the black dust that covers the shell, it looks like charcoal. I place them on a stone and, with a smaller stone, I crack them. Inside, the small yellowish seed is covered by a thin, crispy skin that crumbles when I touch it. I eat it, savour it, it is so good! I still remember that pine forest taste, as if all the sensations I experienced there were contained in each pine nut I ate. We chew, savour, and feel within us the offering. Giving and receiving, receiving and giving.

Accompanied by this memory, I begin the path of this project, in the place where I live, within the community of beings of which I am a part. I propose to learn about the edible plants of the valley and its surroundings, to learn to receive and give, and to represent this journey through drawing. To also learn to care.

After many wanderings through the valley, conversations and moments of silence, observations, drawings, readings, and other investigations, I found 32 plants that are edible. From this set, I chose 23 plants because they are the ones I have a longer relationship with. I have accompanied them through the seasons of the year, in the rhythms of the valley, in sun and rain. I know how they are born, grow, and die. I know their morphology, the places where they live, their relationships with other beings. We have been conversing together for a few years. The remaining 9 will be part of the near future, but I need to know them better. Some are in places inaccessible to me; I only saw them from a distance. Others, I saw in spring in bloom; I don’t know how they survive the winter. It takes time to get to know another being.

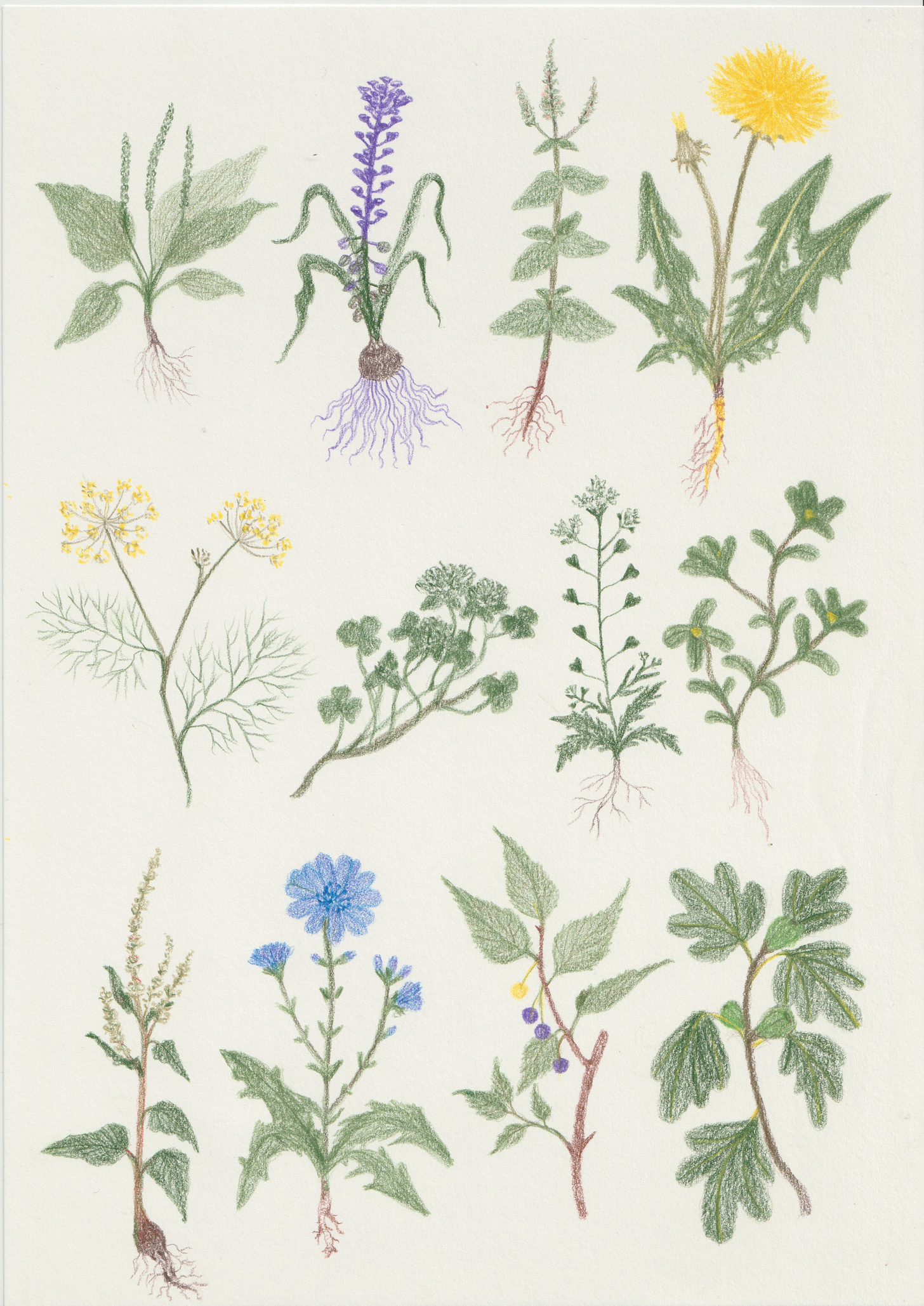

I present to you the 23 plants of this “Edible Herbarium – a learning journey”:

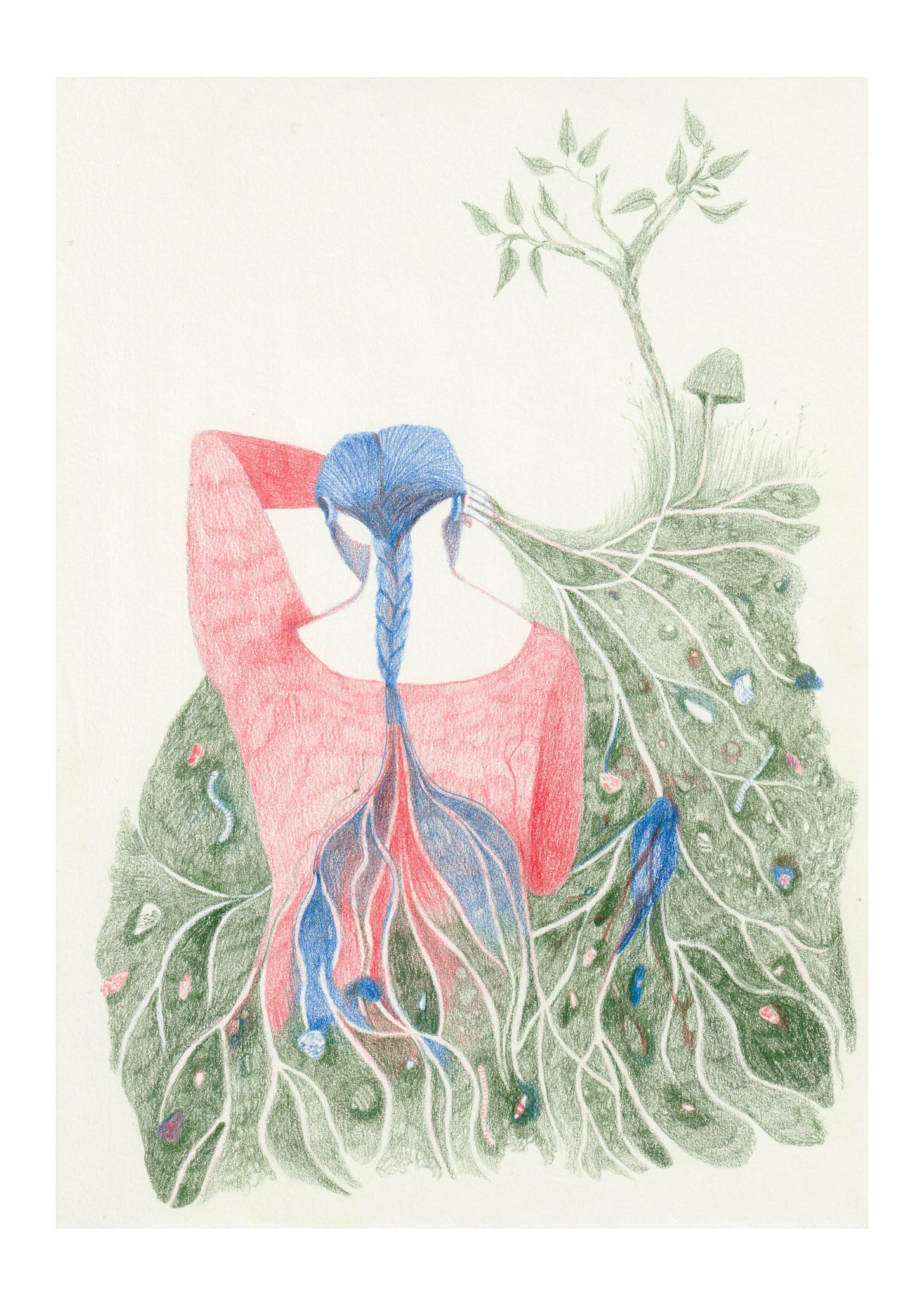

(First drawing - from left to right, from top to bottom)

Plantago major, Broadleaf plantain

Edible parts - leaves and seeds, in salads (when the leaves are tender), soups, stir-fried and in stews. Ground seeds can be added to bread dough. It is also a medicinal plant.

Muscari cosmosum, Tassel hyacinth

Edible parts - bulb, tastes similar to onion and garlic, in salads or cooked.

Menta suaveolens, Apple mint

Edible parts - leaves, used to flavor salads, sautéed dishes, soups, juices, and refreshments, in teas. It is also a medicinal plant.

Taraxacum officinalis, Common dandelion

Edible parts - leaves, roots, and flowers. The leaves can be used in salads, soups, stir-fries, and stews. The flowers are used in salads and beverages. The roots can be roasted and seasoned as a snack, or dried, roasted, and ground as a coffee substitute drink. It is also a medicinal plant.

Foeniculum vulgare, Fennel

Edible parts - leaves, fruits, and seeds. Leaves and petioles chopped as a seasoning for sauces, soups, and stir-fries; the thick base of the leaves can be cooked and used in soups. The fruits have a savory flavor and can be used in liqueurs. The dried seeds are used to flavor stews and beverages, and can also be used to make tea. It is also a medicinal plant.

Trifolium repens, White clover

Edible parts - leaves and flowers. Leaves can be used in salads and stir-fries, while the flowers, which have a vanilla aroma, can be used in salads and teas. It is also a medicinal plant.

Capsella bursa pastoris, Shepherd’s purse

Edible parts - basal leaves, in salads or cooked.

Portucala oleracea, Little hogweed or Pursley

Edible parts - leaves, in salads and soups. It is also a medicinal plant.

Beta maritima, Sea beet

Edible parts - leaves, in salads (young leaves), in soups, sautéed, or in purées.

Cichorium intybus, Common chicory

Edible parts - roots, basal leaves, and stems; leaves in salads and soups; stems cooked and sautéed; roots dried, roasted, and ground to make a coffee substitute beverage. It is also a medicinal plant.

Celtis australis, European nettle tree, Mediterranean hackberry

Edible parts - fruits, small berries with a sweet flavor similar to cherries. It is also a medicinal plant.

Ficus-carica, Fig plant

Edible parts - fruit and leaves; fruit eaten alone or with salads and cheese, leaves used in tea or as wrappers for other foods. It is also a medicinal plant.

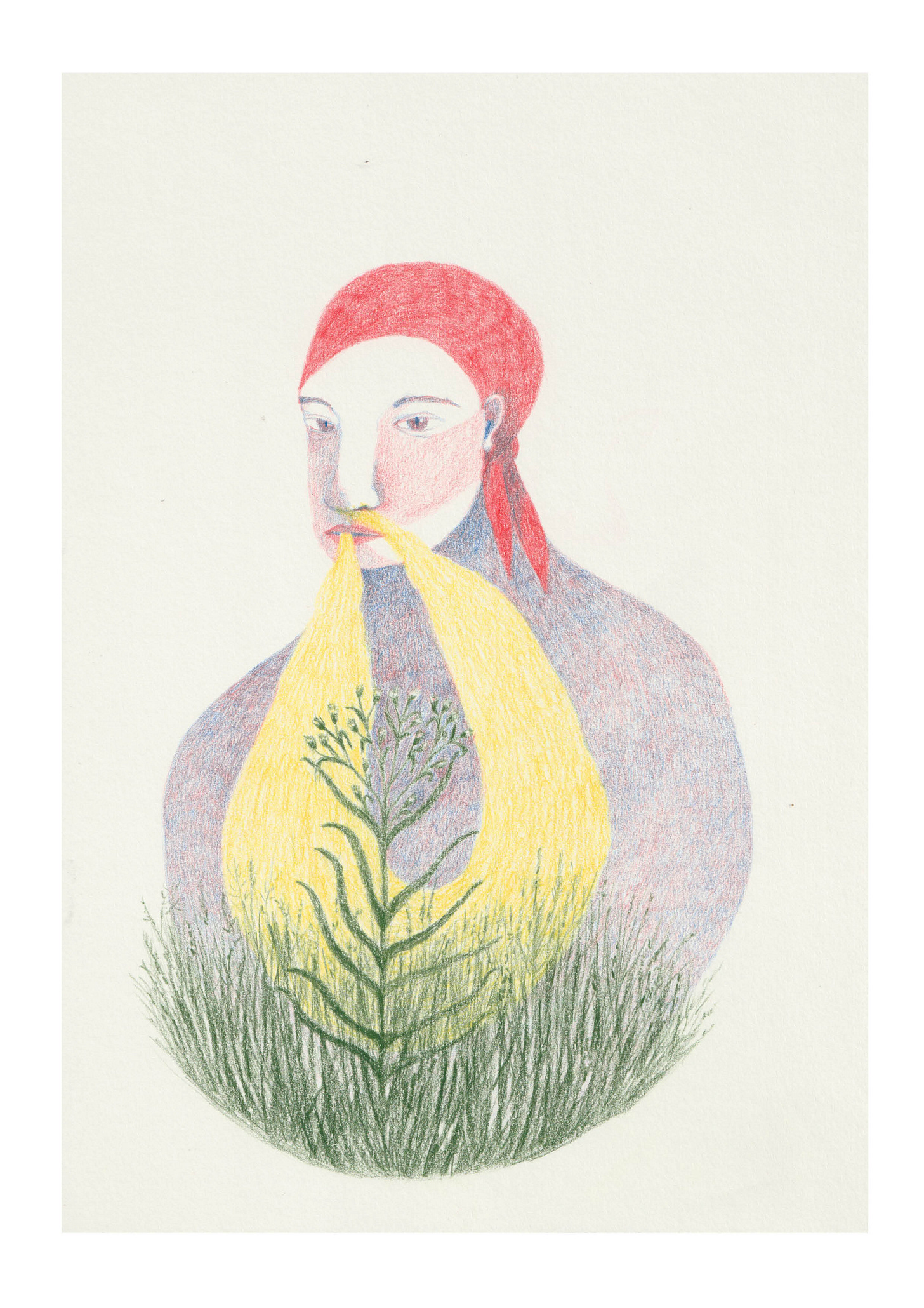

(Second drawing - from left to right, from top to bottom)

Allium ampelorrasum, Wild leek

Edible parts - roots, leaves, and stem; the bulb, the white part of the root tastes like a mix of garlic and onion, can be used to season sauces, salads, sautés, and soups; leaves cooked in soups and stews.

Papaver rhoeas, Common poppy

Edible parts - seeds, can be ground and toasted for use in breads and cakes. It is also a medicinal plant.

Urtica dioica, Common nettle

Edible parts - leaves, cooked and used in soups and purées. It is also a medicinal plant.

Borago officinalis, Starflower

Edible parts - leaves and flowers; leaves in salads, soups, and sautés, with a fresh taste; also used in juices when young. Flowers are sweet and used in salads, desserts, and beverages. It is also a medicinal plant.

Plantago lanceolata, Ribwort plantain, Lamb’s tongue

Edible parts - leaves, the tender ones in salads, cooked in soups, stews, and stir-fries. It is also a medicinal plant.

Smyrnium olusatrum, Alexanders

Edible parts - all parts are edible; leaves and stems cooked in soups and stews, similar in taste to celery and parsley. Young and tender leaves in salads and stir-fries; seeds have a spicy flavor.

Oxalis pes-capre, Bermuda buttercup, Sourgrass

Edible parts - roots and flowers; the white part of the root can be roasted in the oven, seasoned, and eaten as an appetizer; flowers in salads should be used in moderation.

Malva sylvestris, Common mallow

Edible parts - young leaves, flowers, fruits, and roots; the leaves have thickening properties, used in sauces, soups, and stews. Flower petals flavor salads and desserts; unripe fruits (“cheeses”) in salads. It is also a medicinal plant.

Pinus pinea, Mediterranean stone pine

Edible parts - seeds, the pine nut can be eaten directly or used in pastries, salads, sauces, and main dishes. It is also a medicinal plant.

Quercus rotundifolia, Holm oak, Ballota oak

Edible parts - fruits, acorns can be roasted and also ground to make flour used in bread and cakes. It is also a medicinal plant.

Olea europea, Olive tree

Edible parts - fruits, olives are used to make olive oil; when cured and seasoned, they can also be eaten as an appetizer. It is also a medicinal plant.

*

Drawing this herbarium is to be and think with the plants, learning to recognize their singularities; each plant is a being. In representing this dialogue through drawing, I explore our relationship, learning how these plants provide sustenance and food.

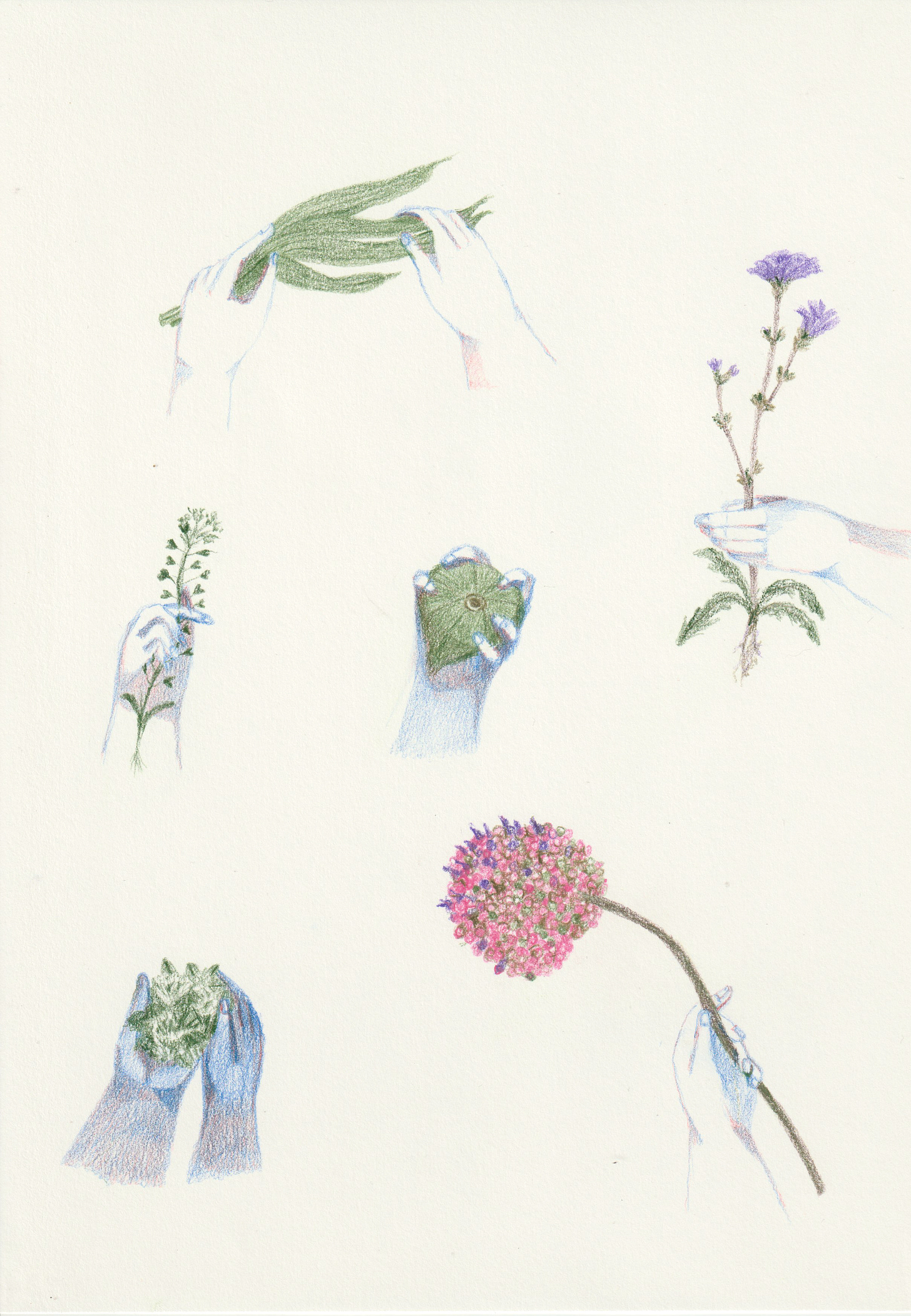

Perception is my first approach; with the practice of drawing, the sensory experience begins with seeing, it is visual. I follow with my gaze their morphologies, seeing them sway in the wind; we are in Spring, and the colors stand out—pink, lilac, yellow, white, red, blue; the plants have bloomed, and I know that in a few months everything will change. Birds and insects flutter around me, feeding on these plants. I also accept their offerings and approach. To taste, I have to harvest, and touch is the second sense I use: in my hands, I feel the soft leaves of broadleaf plantain and lamb’s tongue, the delicate petals of poppies; I notice the rough contrast when I touch the trunks of olive and holm oak trees; I marvel at the elasticity of dandelion stems. I become aware of their fragilities and strengths when I harvest them, observing the roots and understanding their connections to the earth. If I am attentive, I hear the seeds of poppies and shepherd’s purse popping. So close to them and immersed in their place, I smell the acrid and sweet scent of the wild leek and the freshness of sourgrass. The sense of smell awakens my curiosity for taste, and when taste and flavor join, the five senses begin a new melody that I start to discover; sensations expand and vibrate. When I return to the first sense and see the plant I hold in my hands, I know that our conversation has deepened, and my entire sensory perception has participated in it. With its offering, this being that I now know better has nourished me, and in the moment I eat it, I am reconnected to the earth and all beings around me. Eating is participating in a whole, sharing, knowing, because our being participates entirely in this individual and communal relationship; eating is culture.

“The notion of the Anthropocene transforms what defines the very existence of the world into a singular, historical, and negative action: it makes nature a cultural exception and man an extranatural cause. Above all, it neglects the fact that the world is always the reality of the breath of the living.

Cosmology, in this sense, is a pneumatology, or rather, it is its supreme form. To know the world is to breathe it, since all breathing is a production of the world: what appears to be separate comes together in a dynamic unity. To breathe means to taste the world.”

Emanuele Coccia, “The Life of Plants: A Metaphysics of Mixture”

“It is time to extend his call for a conspiracy of breathers to include the plants. That is, we need to learn not just how to collaborate, but also how to conspire with the plants, to breathe with them. Remember, they breathed us into being.

Remember this: what is good for plants is good for everyone else. Get on their side. Consider yourself at their service. Get to know plants intimately and on their terms.”

Natasha Myres, “How to grow liveable worlds: Ten (not-so-easy) steps for life in the Planthroposcene”

In these two months, I harvested many of these 23 plants, tasted some at home with my family, and left roots, leaves, and flowers to dry for making drinks and teas. I recalled some flavors because I had tasted them before and now, they were dormant. I learned to understand what they offer us—seeds, leaves, flowers, fruits, stems, roots, and shoots. I now know how to distinguish the parts to harvest, how to do it, and to do it in moderation because it is shared with everyone.

In the practice of preparing and eating them, I experimented with new recipes—salad with sea beet leaves, broadleaf plantain and lamb’s tongue with sourgrass flowers and white clovers, seasoned with garlic, salt, pepper, and olive oil. I discovered new flavors—I enjoy eating the shoots (“cheeses”) of common mallow raw, they have a fresh and lively taste. I used new seasonings—crushed wild leek in sautés; I remembered old flavors that I missed eating again—nettles purée, figs with cottage cheese and honey, pursley soup. I continued habits— drinking wild mint tea with a spoonful of honey; and I am eager to continue trying—alexanders soup with carrot and sweet potato, sea beet leaf rice and dandelion leaf rice sprinkled with their flowers, roasted acorn layered with honey, lemonade with starflowers and honey.

This education from the edible herbarium has broadened my horizons in a sustainable way and within the community of beings of which I am a part. It made me recall knowledge I learned in the past, discover old and local knowledge that had fallen into disuse and use it again. All this practice has become part of our daily lives and rhythms, renewing connections with ancestors and the bonds of sharing they had with the community where they lived. I am creating new food habits that will later become memories, passing them on to my son and sharing them to give them continuity.

The Mediterranean Hackberry that lines the street from below my door to the entrance to the valley bear their ripe fruit in winter. During October and November, their dark purple berries are perfect for eating. One day, as I reached for the berries on the lower branches, I saw through the leaves the yellow beak of a blackbird energetically pecking at a berry on a higher branch. Our eyes met at that moment as we both ate that tiny fruit with a taste like sour cherries. The Mediterranean Hackberry offered us its ripe fruits—three beings, one plant, and two animals—in communion. This event that I recall here is something that expands throughout the community; everyone eats. Throughout the year, these 23 plants that I am now learning to eat are the food for many in the valley and surrounding areas. Blackbirds, sparrows, redstarts, swallows, and many other birds peck at fruits, flowers, and seeds. Grasshoppers and snails taste the fresh, tender leaves that have just sprouted. When winter comes and the holm oaks are laden with acorns, hedgehogs will eat all they find fallen to the ground, and jays will share their labor as it’s time to “stock their pantries.” In this collection, they also reforest because many of the acorns hidden by jays in the earth are not found again and sprout into new holm oak saplings. Bees, butterflies, beetles, and bugs, ladybugs and dragonflies, fly and gather, spreading seeds and pollen as they eat and collect. They receive and give in a movement that unites the entire community, renewing and flourishing. Now, I too harvest and learn to eat within this community. Everyone eats!

I remember that the tiny seed of the Mediterranean Hackberry I ate returned to the earth, that the berry the blackbird pecked eventually released its seed and it also fell to the ground, thus the plant seeds itself. It gives back to the earth that provided it sustenance, creates a new being, renews itself. Giving and receiving, receiving and giving in this infinite circle where all beings are born, live, eat, and die, they are also food, sustenance for others, and they give life. All beings.

Throughout this project, my relationship with the plants, these 23 beings, has deepened. I knew them from all the moments we spent together and from learning to share their rhythms by being present and attentive. But now I know their taste; I have received their offerings; they have been part of my meals, providing sustenance and nourishment. They are a visceral and intrinsic part of me; I am part of them, and through this union, I also belong to the earth, the air, the water, to everything that nourishes them. I merge our breaths and share them with all other beings.

From this broad and immense connection, I imagine stories drawn from a body that is not alone, immersed in community—a body that flourishes and takes root, a body undergoing metamorphoses that expand its singularities. A body that is one and whole simultaneously.

“All flows

Every day brings a new sun.”

Heraclitus, “Hélade – Anthology of Greek Culture”

Bibliography

“It was early” in “Devotions - The Selected Poems of Mary Oliver”, Mary Oliver, Penguin books

“Kincentric ecology: indigenous perceptions of the human-nature relationship”, Enrique Salmón, Department of Anthropology, Fort Lewis College, Durango, Colorado USA

“Thus Spoke the Plant”, Monica Gagliano, North Atlantic books 2018

“A vida das plantas: uma metafísica da mistura”, Emanuele Coccia, Documenta/Fundação Carmona e Costa

“How to grow liveable worlds: Ten (not-so-easy) steps for life in the Planthroposcene”, Natasha Myres in ABC News, 6 January 2021

“Hélade - Antologia de Cultura Grega”, organizada e traduzida do original por Maria Helena Rocha Pereira Coimbra 1959

“Herbario de Plantas Silvestres”, Pierre y Délia Vignes, Larousse 2021

“Plantas Silvestres Comestíveis do Algarve”, Anabela Romano e Sandra Gonçalves, Universidade do Algarve, Faro 2015

Herbário Comestível - uma aprendizagem

Quando era pequena, o pinhal ao lado da casa dos meus tios, onde passava férias, era o meu refúgio. Brincava à solta, corria sobre a caruma, sossegada ouvia os sons do vento e dos pássaros, e em volta dos troncos sólidos e rugosos dos pinheiros, apanhava as pinhas que, com curiosidade, sacudia à procura das suas sementes – os pinhões. Um petisco que saboreava durante as horas que ali passava. Quando via gotas de resina aparecer nas reentrâncias do tronco, tocava-lhes com os meus dedos pequeninos, achava bonito aquele líquido translúcido que parecia mel, e ficava com eles peganhentos e a colarem-se a tudo o que tocava: pó, caruma, terra, musgo. Aquele pinhal é uma memória de amor e conforto que ainda hoje habita em mim, uma comunidade de seres, um lugar seguro onde podia ser eu própria e estar bem. Ainda hoje, se precisar de me acalmar, é a primeira imagem que se forma dentro de mim: a copa de um pinheiro, cheia de agulhas, pinhas e brilhos do sol, o tronco e a minha mão sobre a sua casca, os pés na caruma, sentir o cheiro a musgo e a terra húmida. As outras memórias que tenho, onde o amor se manifesta em conforto, partilha e comida, são com os meus avós, e hoje, já na meia-idade, junto-lhes as que criei na nossa casa com o meu filho.

Moro há seis anos neste espaço urbano (na cidade de Lisboa), ao lado de um pequeno vale atravessado por uma ribeira. Os seres que aqui vivem fazem parte dos meus dias; atravesso-os com eles – as plantas, os pássaros, as rãs e outros animais, as pedras. Estou atenta e presente, também curiosa. Ao longo das estações do ano, aprendo os seus ritmos, partilhamos diálogos silenciosos e momentos diversos da vida: dores, aflições, alegrias. Tantas vezes surpreendem-me com assombro.

“Sometimes I need

only to stand

wherever I am

to be blessed.”

Mary Oliver, from the poem “It was early” in “Devotions - The Selected Poems of Mary Oliver”

Esta comunidade de que faço parte é a minha vivência e os desenhos que crio a expressão dessa experiência de viver aqui - observações e interpretações, também “imaginações” e outras utopias nascem destes momentos comuns.

Esta prática que erraticamente sempre fez parte da minha vida desde criança, consolidou-se com a vinda para este lugar e a convivência com todos os seres que me rodeiam. Faz agora parte da minha vida e é também uma forma de contrariar a alienação e desenraizamento que nos isolam e cercam.

As plantas estão à minha volta, são elas que cumprimento logo pela manhã da janela, saúdam-me, acompanham-me quando caminho pelo vale, estamos sempre lado a lado. Dentro de mim o pinhal, fora de mim todas as plantas. Respiramos juntas, fazem parte de nós, formam a atmosfera, inspiramos e expiramos um sopro comum que nos dá vida. Receber e dar, dar e receber, as plantas alimentam-nos e dão-nos sustento, tratam-nos e cuidam de nós.

“ To all cultures, belief form and explain the human-nature relationship. Beliefs help a person recognize his/her link to the natural world and his/her responsibility to ensure its survival. No person is truly connected to the natural world or to his/her culture if he/she does not maintain physical, social, spiritual, and mental health; together, they form the breath of life. Breath is the matter and energy, which indigenous people believe moves in all living things. Maintaining a balanced and pure human breath also ensures the purity and health os the breath of the natural world.

With the awareness that one’s breath is shared by all surrounding life, that one’s emergence into this world was possibly caused by some of the life-forms around one’s environment, and that one is responsible for its mutual survival, it becomes apparent that it is related to you; that it shares a kinship with you and with all humans, as does a family or tribe. A reciprocal relationship has been fostered with the realization that humans affect nature and nature affect humans. This awareness influences indigenous interactions with the environment. It is these interactions, these cultural practices of living with a place, that are manifestations of kincentric ecology.”

Enrique Salmón, “Kincentric ecology: indigenous perceptions of the human-nature relationship”

“At each inhalation, free oxygen breathed out by plants enters us in all its levity and allows us to convert what we eat into energy. At each exhalation, we let go of carbon dioxide and water, which plants ingeniously combine with a touch of sunlight to make their own food and, once again, more oxygen. Excitedly, she continued by pointing out how we breathe each other in and out of existence, one made by the exhalation of the other.

Arising from perfect stillness, this deep breath os fresh air is the necessary movement that brings innovation and the expression of individuality, where the unique and the separate as the plant and the human are made temporarily possible. And this same inspired movement that generated them also unbinds them, incessantly releasing both the plant and the human into a space where the separate parts are dissolved.”

Monica Gagliano, “Thus Spoke the Plant”

Regresso ao pinhal da infância. Tenho a pinha na minha mão, agito-a e caem três pinhões. Sujo as mãos no pó preto que envolve a casca, parece carvão. Coloco-os sobre uma pedra e, com outra pedra mais pequena, parto-os. Lá dentro, a semente pequenina amarelada está coberta por uma pele fina e estaladiça que se desfaz quando lhe toco. Como-a, saboreio-a, é tão bom! Ainda hoje me lembro daquele sabor a pinhal, como se todas as sensações que vivi ali estivessem contidas em cada pinhão que comia. Mastigamos, saboreamos e sentimos dentro de nós a oferta. Dar e receber, receber e dar.

Acompanhada desta memória, inicio o caminho deste projeto, no lugar onde vivo, com a comunidade de seres de que faço parte. Proponho-me a conhecer as plantas comestíveis do vale e arredores, aprender a receber e dar, e representar este caminho através do desenho. Aprender também a cuidar.

Depois de muitas andanças pelo vale, conversas e momentos de silêncio, observações, desenhos, leituras e outras investigações, encontrei 32 plantas que são comestíveis. Deste conjunto, escolhi 23 plantas porque são as que tenho uma relação mais longa. Acompanhei-as durante as estações do ano, nos ritmos do vale, ao sol e à chuva. Sei como nascem, crescem e morrem. Conheço-lhes a morfologia, os sítios onde vivem, as suas relações com os outros seres. Conversamos juntas há alguns anos. As restantes 9 farão parte de um futuro próximo, mas preciso de as conhecer melhor. Algumas estão em locais inacessíveis para mim, só as avistei ao longe. Outras, vi-as na primavera em flor; não sei como passam o inverno. É preciso tempo para conhecermos outro ser.

Apresento-vos as 23 plantas deste “Herbário comestível – uma aprendizagem”:

(leitura da esquerda para a direita, de cima para baixo)

Plantago major, Tanchagem, Broadleaf plantain

Partes comestíveis - folhas e sementes,

em saladas (quando as folhas estão tenras), sopas, salteada e em guisados.

As sementes moídas podem juntar-se à massa do pão.

Também é uma planta medicinal.

Muscari cosmosum, Jacinto-das-searas, Tassel hyacinth

Partes comestíveis - bolbo, tem um sabor próximo da cebola e só alho, em saladas ou cozinhado.

Menta suaveolens, Hortelã-brava, Apple mint

Partes comestíveis- folhas, aromatizantes de saladas, refogados, sopas, sumos e refrescos, em chás

Também é uma planta medicinal.

Taraxacum officinalis, Dente-de-leão, Common dandelion

Partes comestíveis- folhas, raizes e flores, as folhas em saladas, sopas, salteados e guisados, as flores em saladas e refrescos, as raizes tostadas e temperadas como aperitivo ou secas, tostadas e moídas como bebida substituta do café.

Também é uma planta medicinal.

Foeniculum vulgare, Funcho, Fennel

Partes comestíveis - folhas, frutos e sementes, folhas e pecíolos picados como tempero de molhos, sopas e salteados, base grossa das folhas pode ser cozida e utilizada em sopas, os frutos têm um sabor a anos, podem ser utilizados em licores, as sementes secas para aromatizar guisados e bebidas e para chá.

Também é uma planta medicinal.

Trifolium repens, Trevo-branco, White clover

Partes comestíveis- folhas e flores, folhas em saladas, salteados, as flores tem um aroma a baunilha podem ser usadas em saladas e chás.

Também é uma planta medicinal.

Capsella bursa pastoris, Bolsa-de-pastor, Shepherd's purse

Partes comestíveis- folhas basais, em saladas ou cozinhadas

Portucala oleracea, Beldroega, Little hogweed, or Pursley

Partes comestíveis- folhas, em saladas e sopas.

Também é uma planta medicinal.

Beta maritima, Acelga-brava, Sea beet

Partes comestíveis- folhas, em saladas folhas mais tenras, em sopas, salteados, esparregados.

Cichorium intybus, Chicória-silvestre, Common chicory

Partes comestíveis- raizes, folhas basais e caules, folhas em saladas e sopas, os caules cozidos e salteados, as raizes depois de secas são torradas e moídas e fazem uma bebida substituta do café.

Também é uma planta medicinal.

Celtis australis, Lodão-bastardo, European nettle tree, Mediterranean hackberry

Partes comestíveis- frutos, pequenas bagas com um sabor adocicado parecido com as ginjas.

Também é uma planta medicinal.

Ficus-carica, Figueira, Fig plant

Partes comestíveis- fruto e folhas, o fruto sozinho ou a acompanhar saladas e queijo, folhas em chá ou como invólucros para outras comidas.

Também é uma planta medicinal.

Allium ampelorrasum, Alho-porro-bravo, Wild leek

Partes comestíveis - raízes, folhas e caule, o bolbo, a parte branca da raiz sabe a uma mistura de alho com cebola, pode temperar molhos, saladas, refogados e sopas, as folhas cozidas em sopas e guisados.

Papaver rhoeas, Papoila, Common poppy

Partes comestíveis- sementes, podem ser moídas e torradas e utilizadas em pães e bolos.

Também é uma planta medicinal.

Urtica dioica, Urtiga-brava, Common nettle

Partes comestíveis- folhas, cozidas e usadas em sopas e esparregados.

Também é uma planta medicinal.

Borago officinalis, Borragem, Starflower

Partes comestíveis- folhas e flores, folhas em saladas, sopas e salteados, têm um sabor fresco, também em sumos as folhas pequenas. As flores são doces e usadas em saladas, sobremesas, refrescos.

Também é uma planta medicinal.

Plantago lanceolata, Língua-de-ovelha, Ribwort plantain, Lamb's tongue

Partes comestíveis - folhas, as mais tenras em saladas, cozidas em sopas, guisados e salteados.

Também é uma planta medicinal.

Smyrnium olusatrum, Aipo-dos-cavalos, Alexanders

Partes comestíveis- todas as partes são comestíveis, folhas e caules cozidos em sopas e guisados, tem um sabor parecido com o aipo e a salsa. Folhas jovens e tentas em saladas e salteados, as sementes têm um sabor picante.

Oxalis pes-capre, Azedas, Bermuda buttercup, Sourgrass

Partes comestíveis- raízes e flores, a parte branca da raiz pode ser assada no forno, temperada e comida como um aperitivo, as flores em saladas com moderação.

Malva sylvestris - Malva-silvestre, Common mallow

Partes comestíveis- folhas jovens, flores, frutos e raizes, as folhas têm propriedades espessantes, utilizadas em molhos, sopas e guisados. As pétalas das flores aromatizam saladas e doçaria, os frutos ainda verdes (“queijinhos”) em saladas.

Também é uma planta medicinal.

Pinus pinea, Pinheiro-manso, Mediterranean stone pine

Partes comestíveis- sementes, o pinhão pode ser comido directamente ou utilizado em doçaria, saladas, molhos e pratos principais.

Também é uma planta medicinal.

Quercus rotundifolia, Azinheira, Holm oak, Ballota oak

Partes comestíveis- frutos, a bolota pode ser assada e também moída para confeccionar farinha, utilizada em pão, bolos.

Também é uma planta medicinal.

Olea europea, Oliveira, Olive tree

Partes comestíveis- frutos, as azeitonas são utilizadas para fazer azeite, também curadas e temperadas podem ser comidas como aperitivo.

Também é uma planta medicinal.

*

Desenhar este herbário é estar e pensar com as plantas, aprender a reconhecer as suas singularidades, cada planta é um ser. Na representação deste diálogo, através do desenho, investigo a nossa relação, aprendo como estas plantas dão sustento e alimento.

A percepção é a minha primeira aproximação, com a prática do desenho, a experiência sensorial inicia-se com o ver, é visual. Sigo com o olhar as suas morfologias, vejo-as oscilarem com o vento, estamos na Primavera e as cores destacam-se, rosa, lilás, amarelo, branco, vermelho, azul, as plantas floresceram e sei que daqui a alguns meses tudo irá mudar. Os pássaros e os insectos esvoaçam à minha volta, alimentam-se destas plantas. Aceito também as suas ofertas e aproximo-me. Para provar tenho de colher e o tacto é o segundo sentido que utilizo: nas minhas mãos sinto as folhas suaves da tanchagem e da língua-de-ovelha, as pétalas delicadas das papoilas, noto o contraste rugoso quando toco nos troncos das oliveiras e das azinheiras, espanto-me com a elasticidade dos caules dos dente-de-leão. Apercebo-me das suas fragilidades e das suas forças quando as colho, observo as raízes e entendo as suas ligações à terra. Se estiver atenta ouço as sementes de papoila e da bolsa-de-pastor a estalarem. Tão perto delas e imersa no seu lugar sinto o cheiro acre e adocicado do alho-porro e a frescura das azedas. O olfacto desperta-me a curiosidade do sabor e quando se junta o paladar e o gosto, os cinco sentidos iniciam uma melodia nova que começo a descobrir, as sensações expandem-se e vibram. Quando regresso ao primeiro sentido e vejo a planta que tenho nas mãos sei que nossa conversa se adensou e toda a minha percepção sensorial participou nela. Com a sua oferta este ser que conheço agora melhor alimentou-me, e no momento em que o comi religou-me à terra e a todos os seres que estão à minha volta. Comer é participar de um todo, partilhar, conhecer, porque o nosso ser participa inteiro neste relacionamento individual e comunitário, comer é cultura.

“A noção de Antropoceno transforma o que define a própria existência do mundo numa acção única, histórica e negativa: faz da natureza uma excepção cultural e do homem uma causa extranatural. Ela negligencia, sobretudo, o facto de o mundo ser sempre a realidade da respiração dos vivos.

A cosmologia, neste sentido, é uma pneumatologia, ou melhor, é a sua forma suprema. Conhecer o mundo é respirá-lo, já que todo o respirar é uma produção do mundo: o que parece estar separado reúne-se numa unidade dinâmica. Respirar significa saborear o mundo.”

Emanuele Coccia, “A vida das plantas: uma metafísica da mistura”

“It is time to extend his call for a conspiracy of breathers to include the plants. That is, we need to learn not just how to collaborate, but also how to conspire with the plants, to breathe with them. Remember, they breathed us into being.

Remember this: what is good for plants is good for everyone else. Get on their side. Consider yourself at their service. Get to know plants intimately and on their terms.”

Natasha Myres, “How to grow liveable worlds: Ten (not-so-easy) steps for life in the Planthroposcene”

Nestes dois meses colhi muitas destas 23 plantas, provei algumas em casa com a minha família, deixei raízes, folhas e flores a secar para fazer bebidas e chás, recordei alguns sabores porque já antes as tinha provado e agora estavam dormentes. Aprendi a saber o que nos oferecem - sementes, folhas, flores e frutos, caules, raízes e rebentos, sei agora distinguir as partes a colher, como o fazer e a fazê-lo com moderação porque é partilhado com todos.

Na prática de as preparar e comer, experimentei receitas novas - salada de folhas de acelga brava, de tanchagem e de orelha-de-lebre com flores de azedas e trevos-do-campo, temperada com alho, sal, pimenta e azeite; descobri novos sabores - gosto de comer os rebentos (“queijinhos”) das malvas silvestres crus, têm um sabor fresco e vivaz; usei novos temperos - o alho-porro esmagado nos refogados; lembrei-me de sabores antigos que tenho saudades de voltar a comer - esparregado de urtigas, figos com requeijão e mel, sopa de beldroegas; continuei hábitos - beber chá de hortelã-brava com uma colher de mel; e fiquei com vontade de continuar a provar - sopa de aipo-dos-cavalos com cenoura e batata-doce, arroz de folhas de acelga-brava e de folhas de dente-de-leão salpicado com as suas flores, bolota assada no forno às camadas com mel, limonada com flores da borragem e mel.

Esta aprendizagem do herbário comestível alargou os meus horizontes de uma forma sustentável e com a comunidade de seres de que faço parte. Fez-me recordar saberes que aprendi no passado, descobrir saberes antigos e locais que caíram em desuso e utilizá-los novamente. Toda esta prática começou a fazer parte dos nossos dias e dos nossos ritmos e com ela renovo ligações com os antepassados e com os laços de partilha que tinham com a comunidade onde viviam. Crio novos hábitos à volta da comida que mais tarde serão memórias, transmito-as ao meu filho e partilho-as dando-lhes continuidade.

Os lodãos-bastardo que ladeiam a rua desde abaixo da minha porta até à entrada para o vale têm os seus frutos maduros no Inverno. Durante os meses de Outubro e Novembro as suas bagas arroxeadas e escuras estão no ponto para serem comidas. Um dia quando me esticava para alcançar as bagas das ramagens mais baixas, vejo por entre as folhas o bico amarelo de um melro que debicava energicamente uma baga de um ramo mais alto. Encontrámos os nossos olhares naquele momento em que comíamos aquele fruto pequenino com sabor a ginja. O lodão-bastardo oferecia-nos os seus frutos maduros, três seres, uma planta e dois animais, em comunhão. Este acontecimento que recordo aqui é algo que se expande pela comunidade, todos comem. Durante o ano, estas 23 plantas que aprendo agora a comer, são o alimento de muitos no vale e arredores. Os melros, os pardais e os rabirruivos, as andorinhas e tantos outros pássaros debicam frutos, flores e sementes. Os gafanhotos e os caracóis provam as folhas frescas e tenras que acabaram de nascer. Quando chegar o Inverno e as azinheiras estiverem carregadas de bolotas os ouriços-caixeiros irão comer todas as que encontrarem caídas no solo, e os gaios partilharão o seu labor pois é altura de “encherem as suas despensas” e nesta colecta reflorestam porque muitas das bolotas que os gaios escondem na terra não são reencontraras e brotam em rebentos de novas azinheiras. As abelhas, as borboletas, os escaravelhos e os besouros, as joaninhas e as libelinhas voam e colhem e enquanto comem e recolhem espalham as sementes e os pólens. Recebem e dão num movimento que une toda a comunidade que se renova e floresce. Agora também eu colho e aprendo a comer em comunidade. Todos comem!

Recordo-me que o caroço minúsculo da baga do lodão-bastardo que comi voltou à terra, que a baga que o melro debicou acabou por soltar o seu caroço e este caiu também na terra e a planta assim semeia. Devolve à terra que lhe deu sustento, cria um novo ser, renova-se. Dar e receber, receber e dar neste círculo infinito onde todos os seres nascem, vivem, comem e morrem, são também alimento, comida para outros e dão vida. Todos os seres.

No decorrer deste projeto a minha relação com as plantas, estes 23 seres, aprofundou-se. Conhecia-as de todos os momentos em que estivemos juntas e de aprender a partilhar os seus ritmos estando presente e atenta, mas agora sei o seu sabor, recebi as suas ofertas, fizeram parte das minhas refeições, foram sustento, comida. Fazem parte de mim de uma forma visceral e intrínseca, eu faço parte delas, e através desta união faço também parte da terra, do ar, da água, de tudo o que as alimenta, junto as nossas respirações e partilho-as com todos os outros seres.

A partir desta ligação ampla e imensa imagino histórias desenhadas de um corpo que não está sozinho, que está imerso na comunidade, um corpo que floresce e que cria raízes, um corpo em metamorfoses que expandem as suas singularidades. Um corpo que é um e todo simultaneamente.

“ Tudo flui

Todos os dias há um sol novo.”